Less ideation. More repetition.

What you repeat becomes what you’re remembered for... just ask Coca-Cola.

At a certain point, as you advance in your marketing career, the questions most likely change.

Not in scope but in posture. You go from building programs to explaining them. From asking what’s possible to proving what’s working. From defining the strategy to validating the spend.

The conversations start to narrow:

“How does this tie to pipeline?”

“Is it ROI-positive yet?”

“What are we tracking against?”

None of these questions are unreasonable.

In fact, they often come from a good place - an organization trying to stay accountable. But the pressure behind them changes will start to change the way you do things.

It can start to shape the work before the work even begins.

The Shift We Often See

In the earlier stages of a company, marketing is allowed to be exploratory. There’s permission to be directional. An understanding that some investments take time to mature. Leaders accept that not every outcome can be measured within a quarter.

But as the company scales, the need for clarity hardens into a need for certainty.

Budgets tighten. Reporting becomes more demanding.

And slowly, a new standard emerges - one in which every initiative must be defensible in advance.

Forecasts. Attribution logic. Inputs cleanly tied to outputs.

This is often where the tension begins. Not because the work lacks rigor, but because the nature of brand and world building often resists real-time validation.

Campaigns need time to breathe.

Perception doesn’t shift on command.

Consumer behavior - especially around trust - tends to be shaped through repeated exposure, not isolated “touchpoints.”

And this is not a “problem to solve.”

It’s a pattern to understand.

A (Potentially) Helpful Frame: Cognitive Fluency

Cognitive science 🤓 offers a useful lens here. People don’t respond like dashboards. They aren’t linear input-output systems. They’re pattern-seeking. Meaning-making. And meaning, especially in the context of brand recognition, rarely arrives all at once.

Most brand communication is processed through filters:

Distraction. Prior beliefs. Emotional availability. Which means even the most well-crafted message may not land immediately.

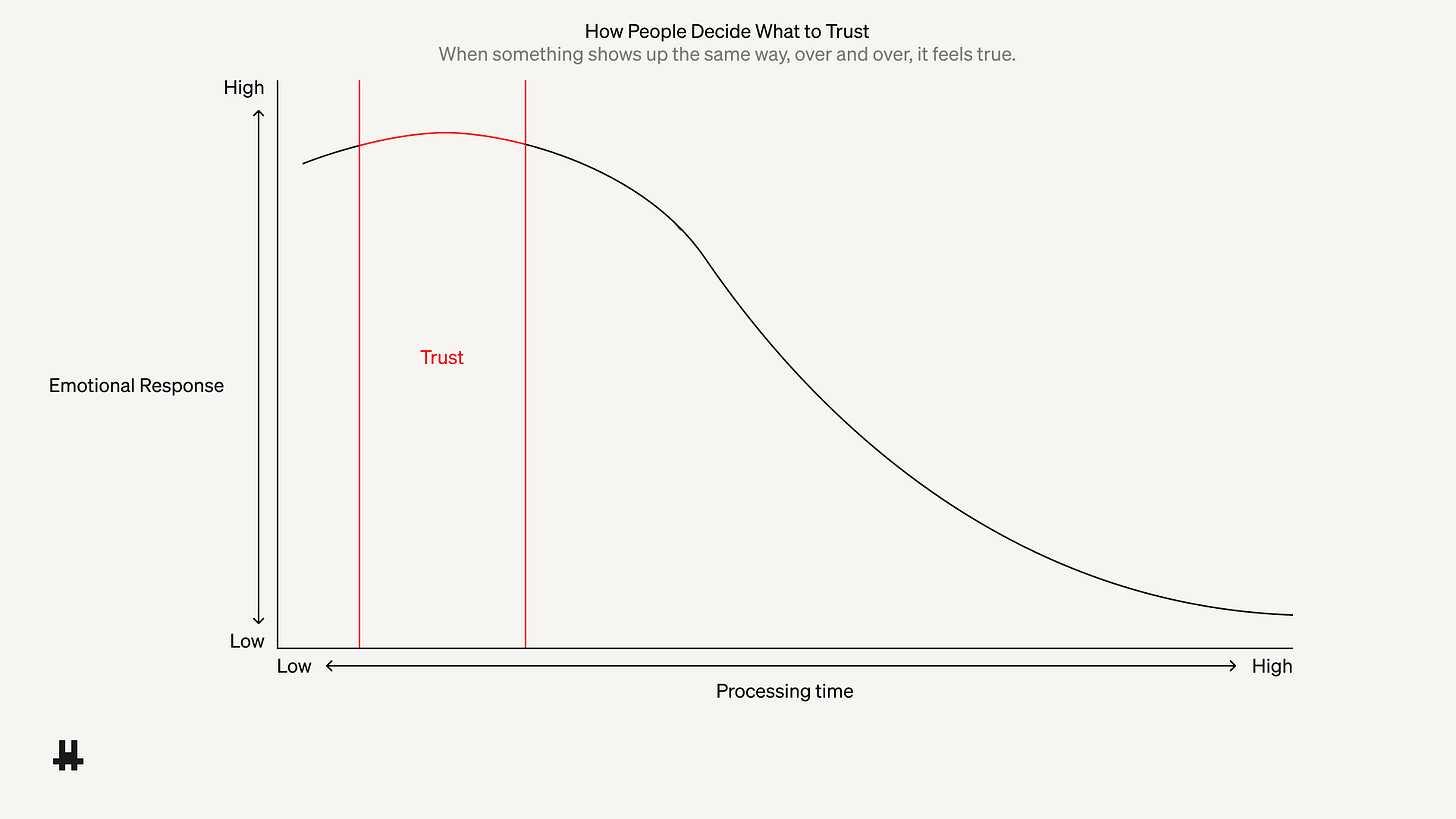

Cognitive fluency - the ease with which we process information - is a key part of this.

When a message is unfamiliar, it creates friction.

The brain has to work harder to understand it. That slows down uptake.

But here’s the upside:

Fluency improves with exposure. Repetition builds recognition. Recognition builds trust. And trust lowers the cognitive load.

The more often your audience encounters consistent cues - tone, language, visual rhythm - the easier it becomes to make sense of them.

Those signals start to feel familiar. Not because they’re simplistic, but because they’re stable. They begin to hold space in the mind rather than needing to be reintroduced each time.

And that consistency does something subtle but powerful.

It makes the brand feel clearer, sooner.

An Example Worth Revisiting: Coca-Cola and Santa

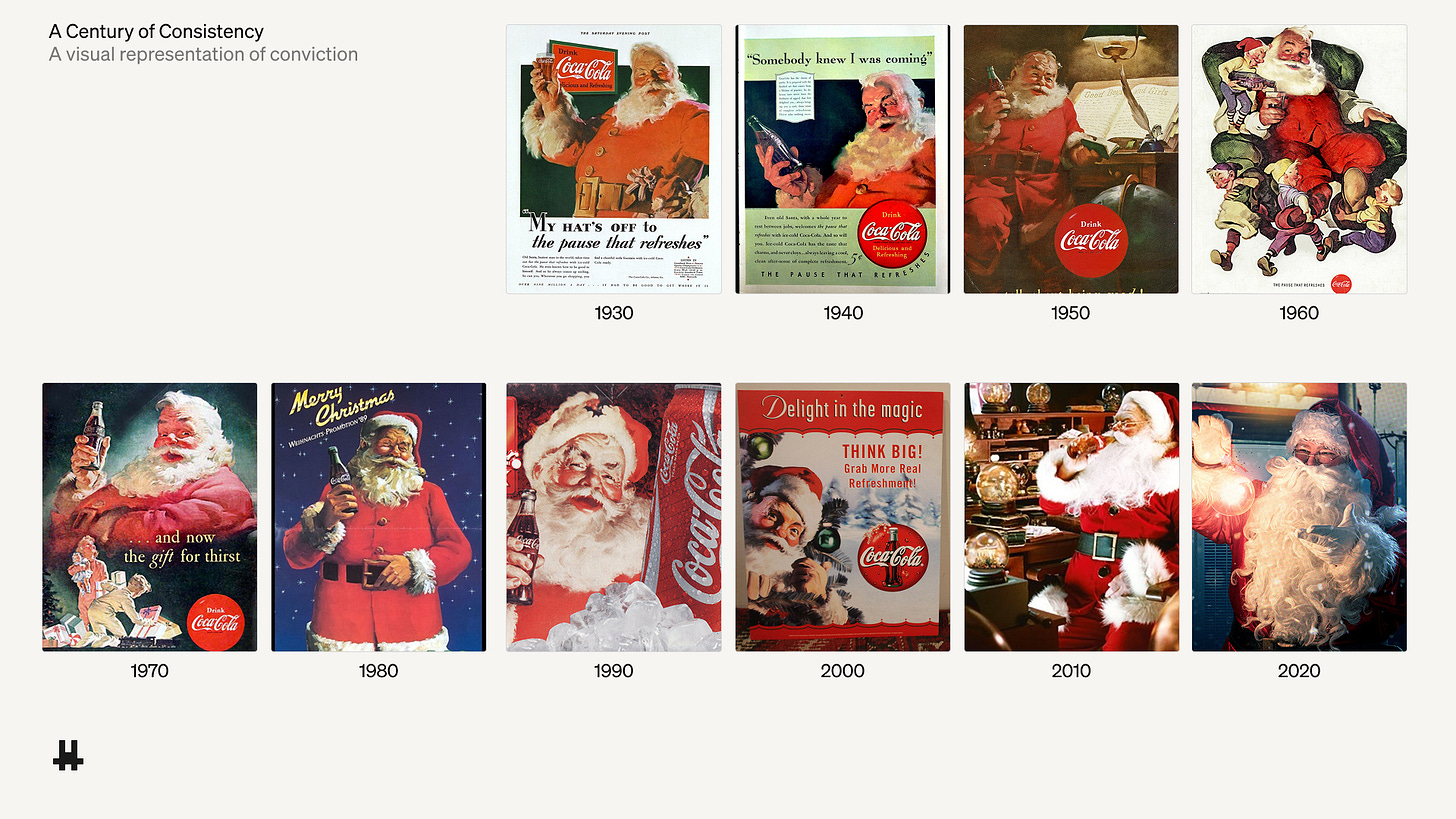

In 1931, Coca-Cola commissioned artist Haddon Sundblom to create a new visual identity for Santa Claus.

At the time, Santa was inconsistent - pure folklore, sometimes tall and thin, sometimes stern, sometimes regal.

Sundblom reimagined him as warm. Jolly. Approachable.

A Santa who smiled. A Santa who held a bottle of Coke.

But the most interesting part isn’t the first painting. It’s what came after.

Sundblom painted a new version of that Santa every year for… over three decades….

Three decades.

Most people wont commit to a message for a 48 hour tik-tok cycle, let alone a half year, or even one full year.

Coca-Cola didn’t chase novelty.

They repeated the signal.

Over and over and over again.

I mean, they have been doing this for nearly 100 years.

Keep in mind, most people want to A/B test and pivot as often as possible.

Maybe that system is the problem?

Maybe adjusting based on immediate reaction isn’t how you build something that lasts.

Early signals are not always the right signals.

With the Coca-Cola Sant, each generation grew up with the same cues: the red suit, the twinkle, the glass bottle. And eventually, those cues stopped feeling like ads.

They became memory.

That’s what consistency does.

It doesn’t just reinforce.

It embeds.

And if anything, today’s fractured attention spans may make consistency more important, not less.

It’s easy to assume that short-form content and constant scrolling demand novelty. But most people aren’t seeking something new. They’re scanning for something they already know. Something they don’t have to work too hard to understand.

Nielsen found that even ad exposures under two seconds can drive nearly 38 percent of brand recall. That’s not because the content is breakthrough. It’s because the brand is familiar enough to register quickly.

As Les Binet, co-author of How Brands Grow, puts it:

“If brands are built over years, why are they managed over quarters?

In other words, short attention spans may make consistency more valuable than ever.

When attention is scattered, the brands that tend to hold space are the ones that offer stable signals - tone, language, visual rhythm - that people already recognize.

This is most likely not because they stand out more. But because they give people something they’ve already come to recognize.

Over time, that recognition does something useful. It makes the work easier to process. Easier to trust. And often, easier to remember.

In that way, consistency isn’t about saying the same thing for its own sake.

It’s about showing up in a way that doesn’t need to be explained from scratch.

Especially in moments when the audience has less attention to give.

A Suggestion for Modern Teams

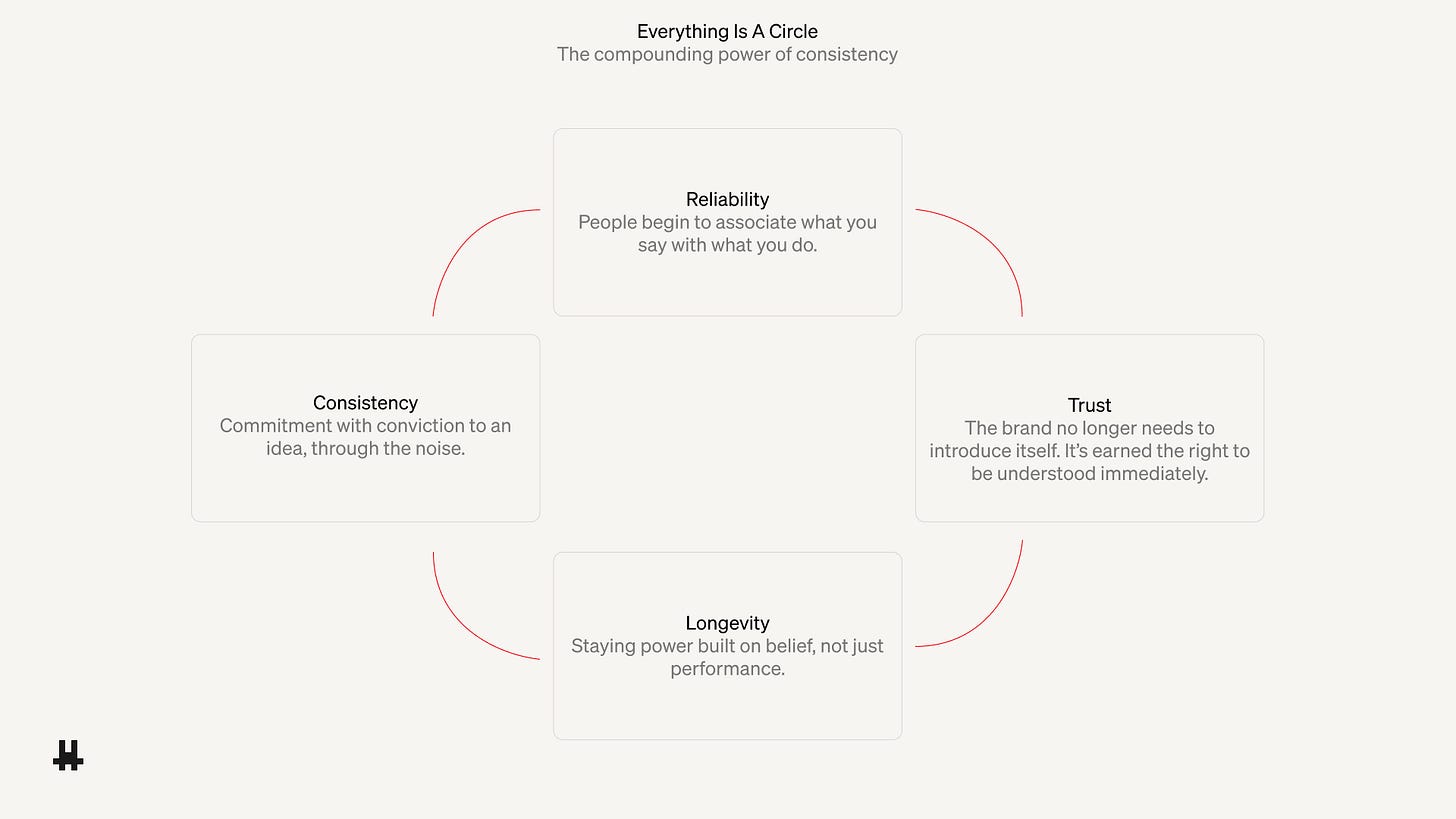

What Coca-Cola did wasn’t a campaign.

It was a 100-year commitment to a single idea.

And belief, especially in the context of brands, isn’t something that tends to flip on overnight. It’s something that accrues. Over time. Through repetition. Through moments of clarity that stack, slowly.

Which is why the push for early validation, while understandable, often backfires. It can force teams to shift priorities too soon.

Messaging becomes narrower, optimized for quick conversion. Budgets skew toward short-term outcomes with clean data trails. Ideas get reshaped to look good on a dashboard.

What gets lost is the thing that often makes marketing effective in the first place:

A sense of direction rooted in audience understanding.

Not just output, but orientation.

What We’ve Noticed in the Teams That Tend to Outperform

In our experience, the difference rarely comes down to raw talent or sharper execution alone.

It often comes down to alignment.

Not alignment as a value on a slide.

But a shared understanding of what the work is for, and how you truly show up everyday.

These teams tend to agree on the business objective behind the initiative. They can point to the audience insight that makes it relevant. They’ve had the conversation about how success should be measured - not just how it could be tracked.

It’s not that they care less about performance. If anything, they’re better equipped to make sense of it. Because the inputs are clearer. The context is already established.

What we’ve found is that clarity tends to create the conditions for better outcomes.

Not in every case. Certainly not always immediately.

But more often than not, alignment gives the work a longer runway and a clearer destination.

Why the Shift Feels Harder at the Senior Level

For senior marketers, the shift isn’t usually about skill. It’s about posture.

You move from being the one doing the work, to the one making sure the work is understood.

It’s less about what’s shipped, and more about whether people believe in what’s being shipped, and why.

That kind of clarity takes time to build. It doesn’t always fit into the slide labeled “Key Results.” And it often can’t be rushed without losing something essential.

But over time, the effects tend to stack. Not because the work moves faster but because it encounters fewer internal contradictions.

That seems to be the discipline Coca-Cola committed to.

They didn’t just invest in a message.

They built belief around it - patiently, repeatedly, and without needing to reinvent it every year.

That kind of discipline may not feel urgent. But for organizations navigating complexity, it tends to hold up longer than most alternatives.

A Final Thought

There’s nothing inherently wrong with chasing novelty.

But novelty tends to fade. Quickly. Sometimes before it even has the chance to register.

What tends to last - what compounds - is familiarity, paired with meaning.

Coca-Cola didn’t win by saying something new every quarter.

They won by making one idea feel familiar enough to trust.

And trust, in the end, is what most brands are really asking for.

Not just attention. But the space to return - again and again - without needing to explain who they are.

That space isn’t earned through speed.

It’s earned through consistency.

And in a landscape built to reward first impressions, that may be what earns second ones.